Dr. Conan Turlough Doyle from Department of Languages and Literature specialises in Old English language and literature, with a focus on early medieval Latin scientific and medical texts. Our students might know him from courses such as Early English Language and Literature and Songs of Love and Chivalry: Arthurian romances of the Middle Ages, where he engages students with readings from classical works, including those that influenced Shakespeare. In our recent interview, Dr. Doyle discussed his forthcoming book, his enduring passion for medieval literature, and his future research plans.

Conan Turlough Doyle

Your research interests are Old English language and literature and early medieval, Latin, scientific and medical literature. Have you been interested in such topics since your childhood or is there any story behind? Were you inspired by any particular historical fact, person, period or book?

I got into it when I was a master’s student. I had always been interested in early literature so for my master's, I studied Old and Middle English. At that time, I was fascinated by the history of witchcraft. I found a book on medical texts and there was a large sort of folk history that the history of medicine and the history of witchcraft are intertwined. The more I learned, the more I realised that this is not exactly correct – there is a link, but it's much more complicated. But when I started reading these Old English medical texts, I realised that they weren't folk-ish. They were very sophisticated, based on Greek medical theory and the theories of Hippocrates, Galenus, and so on. And yet, what was written about these Old English medical texts largely didn't reflect this, but it tried to portray them as a primitive form of practice. And that really has shaped my research interests ever since – what people thought of as quite primitive was quite sophisticated and international. It wasn't an insular phenomenon of some homegrown folklore. It was the same science as was being studied in Paris and Bologna and so on in England in the first millennium.

And witchcraft, is it no longer your subject of interest?

Not specifically. I think my colleagues might know a lot more about it than I do at this point, because witchcraft is really an early modern phenomenon. In the Middle Ages, if you accused someone of witchcraft, you were more likely to be punished by the court for making up lies. But after the Reformation, people started to take the idea of witchcraft much more seriously and to take accusations seriously. That obviously had terrible consequences for the poor people who were accused.

You mentioned that your interest was born during your master's. So before that, you just loved literature?

Not quite. When I was a teenager, I thought I wanted to study natural sciences. But in the last year of high school, I was preparing for the Leaving Certificate, and I just couldn't get enough of Shakespeare. So I decided at the last minute to change my application from natural sciences to literature and English.

…and you never regret it?

Hard question. I don't regret it, because I really love what I do and what I study. However, I think job security is easier in some other disciplines than medieval literature.

What particular topic is your favourite? For research as well as for yourself to explore?

There's a number of topics that I really enjoy exploring. At the moment, since I have finished writing my new book, which is going to be published quite soon, I have begun working on a new idea. That is to trace how the same texts as were used in England in the 10th century also exist in Czech manuscripts of the 14th and 15th century, which is surprisingly late. Finding this continuity contradicts a lot of what I was taught about the history of medicine when I first started studying it. There's an idea that after Arabic texts were translated into Latin, the older Latin texts became obsolete. But that's obviously not the case because people were still studying them, copying them, translating them into Czech and German into the 14th and 15th centuries.

If these books were still used practically as medical recipe books – what about progress and new books?

Oh, there were new books being composed and written at the same time for sure. Of course, there were new ideas that come through and new texts started being translated directly from Greek as well in the 15th century. But what's interesting is that the old books continue to be used for their original purpose.

Do you have a book or literature piece you admire, or which inspires you the most?

That's quite difficult. I read many things and teach a lot of literature; at the moment I'm teaching Sir Gawain and the Green Knight. People often think that medieval literature is very dry and boring, but I think can contain a lot of drama, a lot of things and action. It can also contain a lot of sexual innuendo and sexual suggestion, which can be surprising when you first find it. So I'm trying to figure out a way of explaining that, preferably without scandalising my students. I tried to prepare them for it by showing them a scene from Monty Python and the Holy Grail.

That's perfect!

Monty Python and the Holy Grail is probably a more realistic depiction of medieval literature than any film that tries to take itself seriously, because medieval literature often makes fun of itself and its own tropes. It's much more self-aware than one might think.

You mentioned that there is a new book which should be published soon. What is it about?

The book is about the reception of medical Latin texts in early medieval England up to the year 1100. And one thing that surprised me is that they used genuine Galen of Pergamon. There were not many of his texts available in Latin at the time, but they did use what they had. We can trace the Greek original of Galen into a 5th century Latin translation, into a 10th century English translation, that keeps getting used and reused. So that for me, being able to trace that all the way back to Greek original was quite exciting and not necessarily what I expected when I began the project.

When will the book be published?

It should be out in June or July, so there should be copies of it here on the faculty for the start of the next semester.

How can scholars research such phenomena?

For an enormous amount of time, I have used manuscripts, which I've only been able to use because they are available in digital facsimile. Without it, my whole project would have been impossible. And the project did become difficult, because in 2023 the British Library website was hacked and their whole archive of digitised manuscripts went offline. They've managed to put up only about 10 % of it again. Luckily, I had already made my transcriptions of the most important texts before that. Also, there's a website of all Swiss digitised manuscripts, E-codices, which is a phenomenal resource. Especially the library at St. Gallen contains this amazing collection of texts, no matter what you're interested in. To give an example, it contains some texts in Old Irish, as well as medical and scientific texts dating back to the ninth century.

You are very interdisciplinary, meaning you don't work only with other linguists, literary scholars and historians, but also with archaeologists, physical scientists and medics, don’t you?

Yes, I'm working together with Tomáš Alušík from First Faculty of Medicine of CU, he's been helpful in getting me access to certain archives. So, we went together to the town of Vodňany just before the start of the semester. We took some images of a manuscript there that is not well known. It's an extra witness of something called the Physica Plinii, and also an extra witness of some texts about the medical properties of vegetables and fruits by someone called Quintus Gargilius Martialis. He was a Roman statesman of the third century. So there are really, really old texts in this wonderful little book in Vodňany. We want to analyse the stains and residues of this manuscript together with Lukáš Kučera, and analytical chemist at Olomouc. In fact, I believe ČT24 ran a segment on the news the day we visited Olomouc.

What can link such scholars from different fields? Is it an interest that has to be shared and also a willingness to cooperate?

A willingness to cooperate is very important, and in the case of professor Alušík it was just simple. We attended some conferences, I did some editing of his work in English because he needed a native English speaker, and then we started realising we were both interested in the same thing, so we started working together. This cooperation just grew organically.

Is it hard to find a common ground with experts from different fields?

On a practical level, sometimes it is hard when an esteemed colleague doesn't necessarily feel confident speaking in English, and I can't really talk to them in Czech. Sometimes we might converse a little bit in German. Unfortunately, English really is the international language of scholarship, so if someone wants to talk to a scholar from France or Germany or Ireland or anywhere else, they need to switch to English. In that sense, I have an advantage because my native language is the international standard.

What is it like for you to hear all the possible ways your language spoken?

I find it interesting as a linguist, because something very similar was happening in Latin between the 2nd and 5th centuries. Latin was slowly adopted by many people who spoke it their own way so that it eventually became Spanish, Portuguese, French or Italian languages. It is fascinating being able to watch that happen in real time in English. There are native speakers of English all over India, but they speak many different Englishes. English is their native language, but it sounds very different to my English. And of course there's the Central European English, and that is an interesting one to hear too. Perhaps it's starting to rub off on my speech.

This semester you are teaching about the Middle English Arthurian romances. What kind of overlaps can they have with today?

Linking it to modern society is a very interesting topic! One of the constant things that comes up is the construction of gender roles. Masculinity can be constructed in an extremely toxic way in these texts, but that can also be critiqued. Also gender-based violence can be critiqued in the way it's described, the way characters who commit gender-based violence are punished or not, and I think reflecting on that in Middle English literature is one way of helping us reflect on such topics in modern society. There is, of course, a multiplicity of sexualities represented as well in these texts. It's a little more subtle in Middle English, but in the French version of Sir Landevale (Sir Launfal) by Marie de France, I believe that Queen Guinevere specifically accuses Landevale of being gay, which is a threat to his masculinity and causes him to lose everything he gained from his fairy lover by bragging about her, which he had promised not to do. So yes, there are some very interesting parallels with the modern world and a lot of things we can be taught by these texts.

Is it the interdisciplinary perspective you try to teach your students and skill of connecting intellectual dots?

I try to teach them how to connect the dots for themselves, which is basically critical thinking important in every university subject. Connecting the dots between archaeology and history, for example, comes much more to the fore when I'm teaching medical history than when I'm teaching medieval romances. Actually, I went to a very interesting paper by a postdoc, Liam Waters, talking about material culture in the sagas. So, it is possible to connect material culture and literature, anthropology and literature, and so on.

I know that once you read out the part of a Shakespeare soliloquy and you were surprised by the clapping from your class. Is this the sign of hidden theater talent or is this a consequence of working with literature and learning the most appropriate way of reading out loud specific types of text?

I definitely was a frustrated drama kid: I never really got the chance to play in school plays, because in my schools there were always musicals, and you do not want to hear me attempt to sing. I think I always wanted to act, but I never really got the opportunity.

Would you like to read like this more often during your classes?

I think I do bring a little bit of that to all of my classes, but some more than others. When I'm teaching literature, obviously I take time to show them the sound, the rhythm of a text. When I'm teaching academic writing, it's a little drier.

This year you apply for a GA ČR, is it right? What is the topic of research you are working on and what is your experience with such a process?

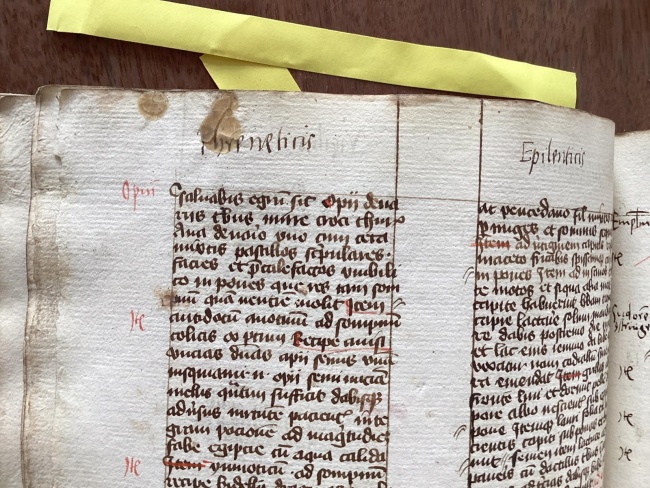

Actually, the research together with Tomáš I described is specifically what I've been preparing to apply with for GA ČR, it's dealing with very ancient texts in late medieval Czech manuscripts. It takes a lot of work just to prepare the proposal, which is where we are now. I have no idea whether it will be successful or not, but even if it's not, we want to do a small amount of what we've promised, so we have more chance of getting the grant next time. We won't just be doing a historic analysis. For example, there's one manuscript we've found already and there are things that seem to be spilled on the pages. What we really want to know is what was spilled, so we've proposed doing some laboratory tests to find out. Was it the very recipes that are on those pages? Was someone trying to make a wax-salve (cerotum) for a burn and then some of it fell on the page? It sounds intriguing, doesn’t it? If we can find that out, that would really change our understanding of how practical these books were.

Spill on the page on the manuscript, photo: archive CTD

Do you work with your students in your researches?

Yes, I've involved some of my students in research. For the last number of years, I've been working on a database, trying to trace texts which have been translated from one language into another. And this database is for work on the Communication in the Middle Ages project, which is a cooperation between Charles University, Háskóli Íslands, and Central European University in Vienna. My dear colleagues, dr. Marie Novotná and prof. Lucie Doležalová, they're the ones who asked me to start work on this database. And because there is so much information that needs to be put in, I have had a number of research assistants from the student body, and it was really nice working with them.

Could your students inspire your work, for example with new questions or different points of view?

Absolutely. Sometimes the best research idea I get is basically a student asking me to explain something better. And then I think, hang on, I do need to explain this better–and that is research. Also, I think research can be improved by teaching in that way, because you don't really understand something until you can explain it to someone else.

My very last – probably not so professional – question. Do you have any funny stories related to the similarity of your name and the name of a famous writer, Conan Doyle?

Well, the day I started my PhD in Cambridge, one of the other people who joined the college on the same day was called Moriarty. This is a true story. We made a joke about how we should probably be enemies, but I didn't see much more of her because we spent time in different departments.

Alena Ivanova

Charles University

Faculty of Humanities

Pátkova 2137/5

182 00 Praha 8 - Libeň

Czech Republic

E-mail: